After over two decades in molecular genetics research, Beverly Akerman realized she’d been learning more and more about less and less. Skittish at the prospect of knowing everything about nothing, she turned, for solace, to writing. The results are impressive: She’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize (fiction and nonfiction) and National Magazine Awards. Her credits include Maclean’s Magazine, The Toronto Star, The National Post, The Montreal Gazette and CBC Radio One’s Sunday Edition, myriad literary and scientific journals and other publications. And, now, she has a collection of short stories titled The Meaning of Children, published with Exile Editions. (Catch Beverly on her blog: http://beverlyakermanmscwriter.blogspot.com/ )

After over two decades in molecular genetics research, Beverly Akerman realized she’d been learning more and more about less and less. Skittish at the prospect of knowing everything about nothing, she turned, for solace, to writing. The results are impressive: She’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize (fiction and nonfiction) and National Magazine Awards. Her credits include Maclean’s Magazine, The Toronto Star, The National Post, The Montreal Gazette and CBC Radio One’s Sunday Edition, myriad literary and scientific journals and other publications. And, now, she has a collection of short stories titled The Meaning of Children, published with Exile Editions. (Catch Beverly on her blog: http://beverlyakermanmscwriter.blogspot.com/ )

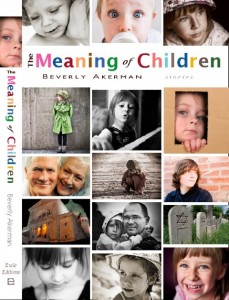

In The Meaning of Children, Beverly presents us with 14 stories that approach the world’s complexities through a child’s eyes (Beginning), grapple with the sorrows and ecstasies of the child-bearing years (Middle), and probe truths that emerge near the end of life’s journey (End). The Meaning of Children speaks to all of us who—though aware the world can be a very dark place—can’t help but long for redemption.

You are a master story teller Beverly. What, in your opinion, makes a great short story and what did you have to pay attention to as a writer?

Everyone’s time is precious, particularly my reader’s. So if I want people to read something I’ve written, there has to be something in it for them. Like, a good story.

I write literary fiction (or try to), but I think some readers (and writers!) have decided that means stories where nothing much happens. Well, in my stories, the kernel is an event that creates a significant emotional response in the reader. I don’t want to spend all my time in a character’s head when I’m reading a book myself, so I’m not going to write stories where the protagonist spends all her time moaning and groaning about her lot. I don’t believe in anomie. I don’t believe in books about nothing more than young people f*cking.

Emotion is important and at the crux of everything. So emotional experiences matter. Paring down the prose matters. Beginning, middle, end. The character has to change (or miss a grand opportunity for growth, and the reader has to know that

Getting a book of short stories published with a prestigious publisher like Exile Editions is everyone’s dream. Tell us a bit about getting them on board.

Getting a book of short stories published with a prestigious publisher like Exile Editions is everyone’s dream. Tell us a bit about getting them on board.

I’m really pleased to be published by Exile for a number of reasons. They’re a small literary publisher with a solid gold reputation—they’ve published some of the great writers of our time— Yehuda Amichai , Pablo Neruda , Morley Callaghan , Austin Clarke , Lauren B. Davis , Michael Moriarty , Joyce Carol Oates , Boris Pasternak , to name a few. But the secret reason I’m thrilled with Exile (I’m a diaspora Jew—even the name “Exile” pleases me!) is that it was founded by Barry Callaghan, who is Morley Callaghan’s son. The current publisher is Michael Callaghan, Barry’s son and Morley’s grandson. But that’s not the secret. The secret is that Morley Callaghan is fundamental to my having become a writer. And in more ways than one.

First of all, his 1951 masterpiece, The Loved and The Lost, has always stuck with me. This great novel of the immorality of racism takes place in Montreal , and the protagonist is a man named Jim McAlpine. TLATL is one of the first CanLit novels I remember reading as a really young person. My last science job ended in 2003, when I left a biotech company called Ecopia. Some time during the last year or so that I worked there, a new VP was recruited from the States, a man named Jim McAlpine.

Now I hadn’t thought of TLATL for years, but the moment I heard the new VP’s name, my first thought was, “that’s the name of Callaghan’s protagonist in TLATL.” I dug up my old copy of the book and brought it into work, where it sat in my desk drawer for months (I never worked up the nerve to show the biochemist Jim McAlpine; I figured he’d think I was a loon!). Every time I caught sight of it, I puzzled over the coincidence of the names and why it meant so much to me. Eventually, I realized that I had to quit science because what I really wanted to do was write.

So Morley Callaghan taught me two absolutely vital things: that the place I lived could be interesting enough to sustain a Governor General Award-winning novel—remember, this was before I’d ever read anything by Richler!—and that a novel I hadn’t looked at for a couple of decades still meant that much to me.

There was one more really fundamental thing that put me on the path to being a writer: the death of my father-in-law, Gerry Copeman. Gerry and I didn’t get along that well, though we’d made our peace. But when he died, I plunged into a crisis: I understood—emotionally, as opposed to rationally or intellectually—that my time on this earth was finite, and I’d better use it doing something I’d always dreamed of doing—which was writing fiction.

Let me take another stab at answering your question, though. I submitted to Exile more than once. I just kept at it. They had my manuscript for close to 2 years, without a contract. The length of time I found very trying, I can’t deny it. But, if there’s a message here, it’s to believe in your work and not give up.

And, by the way, as far as submitting short stories goes, I submitted like mad. And I pretty much completely disregarded any demands not to submit simultaneously—that is, I submitted each story to many lit journals at the same time. That’s supposed to be a no-no. But really, if I needed to face 10 rejections before an acceptance (and that’d be an easy road for most of my stories!), and each journal took six months to answer me, that’d be five years before I got a story accepted…at that rate, I’d’ve been DEAD before having a significant body of stories in print!

Thanks so much Beverly! Remember to send questions to Beverly (or comments about her post). It’s as simple as ABC. Simply click on “Comments.”

Great profile, Sandra.

And kudos to Beverly Akerman for believing in herself and not giving up! What tenacity! You have much more patience than I do.

Doreen, you are bang on. Also, I’m intrigued by Beverly’s approach re: multiple submissions. It’s always annoyed me that lit journals take the approach “thou shalt not make multiple submissions” … very narrow and self-serving. BUT. Was always afraid to get my knuckles rapped. I’m now going to throw get brave and just get my stuff out there. Thanks Beverly!

Yes, be brave! What’s the worst thing that can happen? They don’t publish you!